200 years ago, John Neal set out to tell the world what a real Mainer is

200 years later, we're still re-imagining it.

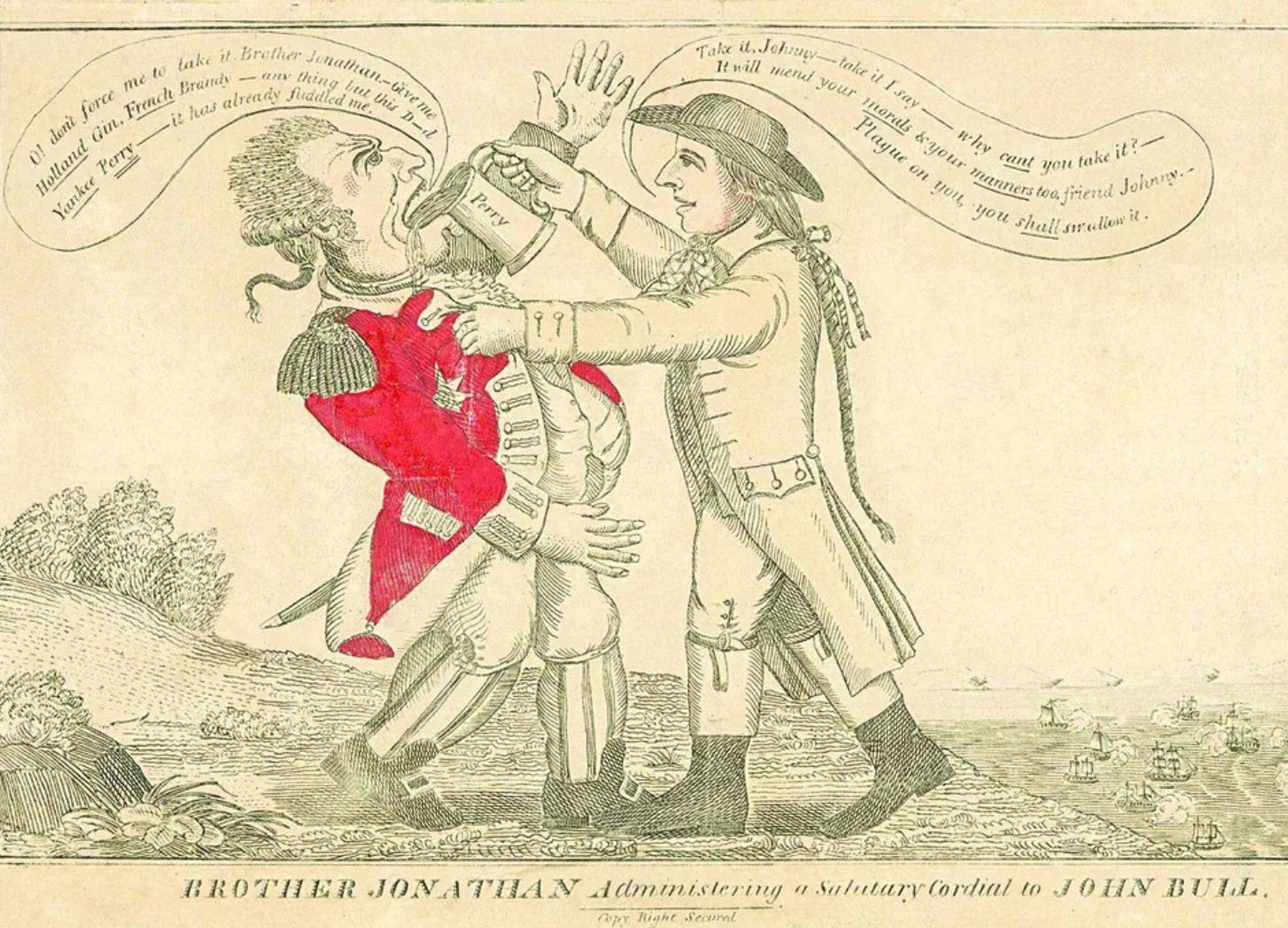

“Is the language here put into the mouth of the New Englander that which is heard in real life? Are the manners here ascribed to him characteristic? However p…