Greed and a wild imagination created Norumbega, Bangor's 'city of gold'

You'll believe anything if you want it badly enough

In the 16th century, Spanish conquistadors and colonizers in South America believed that somewhere out in the continent’s vast jungles, mountains and grasslands there lay the city of El Dorado. The legendary “city of gold,” containing endless riches just waiting for greedy, treasure-mad Spaniards to plunder, was somewhere out there - no matter the fact that, if those riches did exist, they clearly belonged to the people that already lived there.

At the same time, thousands of miles north, a nearly identical thing was occurring. Amid the monumental pine forests, rushing rivers and jagged, rocky coastline of what is now Maine, French and Portuguese explorers and colonizers were searching for the northern version of El Dorado: Norumbega, a bejeweled paradise hidden somewhere in the great north woods.

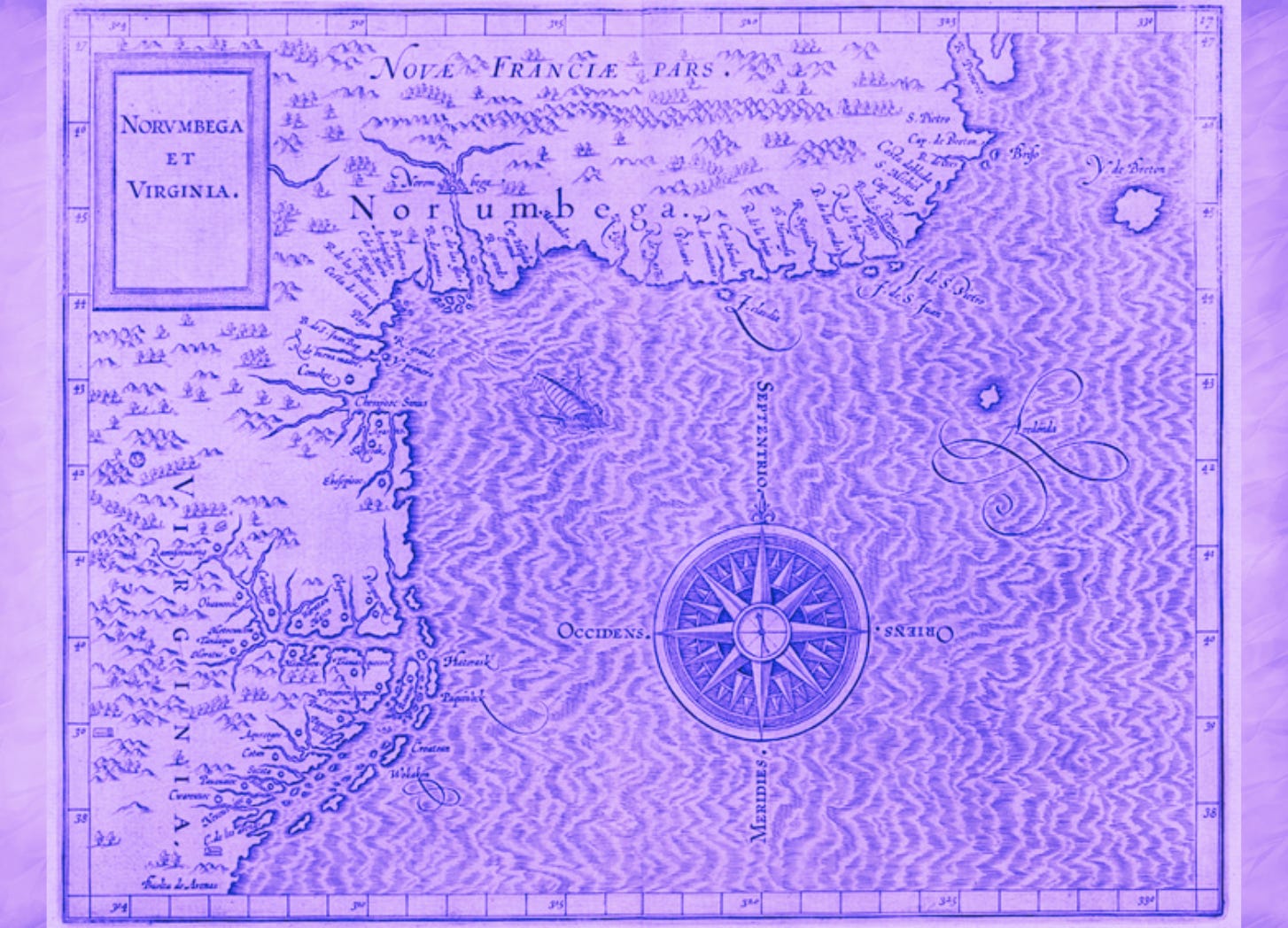

Norumbega - a place-name believed to be either a European corruption of a Wabanaki word referring to the Penobscot River, or, as one scholar claims, Italian for “no quarrel for gold” - was first drawn on a map in 1529 as “Oranbega,” by Giovanni da Verazzanno, the first European to explore the Atlantic Coast south of what is now New Brunswick. By the 1540s, as more Europeans began exploring the region, the word morphed into “Norumbega.”

Maps and documents from that era are full of speculation, but somehow, the 16th century explorers that mapped the Wabanaki land in what is now Maine decided that Norumbega lay along the Penobscot River - specifically, where the city of Bangor lies today.

Why Bangor? It’s never been entirely clear, but the fact that many of these maps placed Norumbega south of Newfoundland and north of what is now New York Harbor, near the mouth of a great river that emptied into a bay full of islands, points convincingly to the Penobscot River and its bay.

European colonizers were as obsessed with finding gold, silver and other riches in the continents they’d inadvertently come across as they were with finding the new trade routes to China and the East Indies they’d ostensibly made the journeys for. As they sailed and trekked on into territory that was unknown to them, wild stories soon followed.

Explorers and cartographers imagined Norumbega as, variously, an island, a city and an entire region. To some, it was a lost civilization, populated by far-flung descendents of ancient Greece. To others, it was more like Atlantis, or other mythical lands. One map from the 1590s marked Norumbega with an icon of a fortified castle - the same sort of marking used for cities like Paris or London - as if it were a major world capital. As the legend spread among sailors from various European nations, the stories grew even wilder - and few were wilder than those concocted by English sailor David Ingram.

In 1567, Ingram was a young man signed with English privateer John Hawkins, a ruthless slave trader who kidnapped people from West Africa and sold them into bondage in European colonies in the Americas. Such was Hawkins’ disregard for human life that when his fleet was attacked off the coast of the Mexican city of Tampico by the Spanish in 1568, Hawkins opted to abandon most of his crew there - including Ingram - to fend for themselves.

The story goes that Ingram and some of his fellow crew members decided to make their way to the English fishing villages in Newfoundland, some 3,000 miles north - a distance the sailors weren’t aware of as they set out on foot to make the journey, given the inaccuracies of the maps available in that era.

Amazingly, Ingram and two others managed to actually do it. 11 months later, in 1569 they arrived - still on foot - in what is now Maine. Or, as Ingram called it when he recounted his story years later: Norumbega.

Ingram and his companions eventually flagged down a passing French vessel, which took them back to the other side of the Atlantic. By the time Ingram finally returned to England, everyone he encountered was eager to hear his tales of what, to them, was the New World - an exotic, alien land full of unknown riches and peoples. He regaled people like John Dee, an occultist and Queen Elizabeth’s personal astrologer, and Sir Francis Walsingham, Elizabeth’s spymaster. Ingram’s stories eventually were published in 1589 by writer Richard Hakluyt, and distributed throughout England and other parts of Europe.

Ingram - and Hakluyt - embellished things just a tad. Not only did Ingram tell people he’d been to the fabled Norumbega - he described a kingdom so overflowing with wealth and resources and populated by such peaceful people that it was, essentially, paradise on Earth.

The great city along the Penobscot was bigger than London, he claimed, with massive paved streets and people hardly able to walk given the amount of gold and silver ornaments they wore. Houses were built out of crystal and precious metals, and massive pearls and rubies littered every street corner. Giant birds the size of a human, crimson-red sheep and beasts with their eyes and mouth in their chest roamed the countryside. Ingram claimed the king of Norumbega was named Bathshaba, and that he took the weary English traveler in and outfitted him with furs and a house to live in.

In other words: Norumbega sure was something else. As one Smithsonian anthropologist would later say, “[Ingram had] probably been cadging food and drink with his story for years, the wonders growing with every telling.”

The myth didn’t last much longer. During Samuel de Champlain’s 1604 expedition up the Penobscot River, the crew found lots of Wabanaki villages and agricultural and fishing infrastructure. It didn’t find houses made of crystal and streets lined with pearls. By the 1620s, the city of Norumbega - like El Dorado, sea serpents and mermaids - had largely disappeared from maps. There was a brief period in the late 19th century when a Harvard scientist claimed that actually, the Norumbega myth came from early Viking exploration of what is now Massachusetts, though that too, was quickly debunked. It’s now just another odd part of the long, bloody legacy of colonialism in the Americas.

And yet, the legacy of that greed-fueled fantasyland continued to inform storytelling and mythologizing about the Bangor region, and academic research in more recent decades has suggested Ingram’s tales of North America are much more plausible than previously thought. In a 2023 book, archaeologist and historian Dean Snow - a former researcher at the University of Maine - claims that while Hakluyt’s book on Ingram is rife with inaccuracies, other contemporary tellings of Ingram’s tale make it clear that his 3,000 mile journey did likely happen, and that his testimony on the peoples of West Africa, the Caribbean, and eastern North America are vital records from the 16th century.

In Maine, the name Norumbega is used for all sorts of things - from a castle-like mansion in Camden that’s now a swanky hotel, to Norumbega Hall in Bangor, a municipal venue for entertainment and sports that burned down in the Great Fire of 1911. It stood where Norumbega Parkway, the green space along the Kenduskeag Stream in downtown Bangor, now lies today. The Chateau Ballroom, a venue built to replace the one that burned, was renamed Norumbega Hall in the 1990s, and now houses the Zillman Art Museum. Norumbega Mountain is a popular hiking destination in Acadia National Park. The name has been variously used in Bangor for a women’s club, a writing collective, a restaurant and a financial firm. Nobody believes Norumbega existed, but plenty like to use it to evoke a mythical past.

Norumbega - and all the other cities of gold that have tantalized explorers for centuries - is a nice idea, to be sure. Endless, easy riches at your fingertips (nevermind the people that already live there). Whether it’s searching for a fantastic land full of fist-sized rubies and streets paved with pearls, or actual attempts to plunder countries that are very much in the realm of reality, unchecked greed and an active imagination are a powerful combination.

This story has always fascinated me, i'm thrilled you dug into it. I have a print of the Champlain map (1607) that shows Norumbega closer to the mouth of the Penobscot River, near or at Verona Island.

great history lesson. Thanks