How do you get to Sardineland?

Take a time machine - or visit the Penobscot Marine Museum in Searsport

For the better part of two years, Cipperly Good’s professional life has been dominated by the big effect one tiny fish has had on Maine: sardines.

Good, curator of maritime history at the Penobscot Marine Museum in Searsport, will see the 2025 season for the museum come to a fishy conclusion with Sardine Fest, a day-long festival set for this weekend, Oct. 4 across the museum’s 3-acre campus. It’ll cap off the first year of its two-year exhibit, “Sardineland,” before the museum closes for the season on Oct. 11.

Through artifacts, documents, photos, personal stories and more, “Sardineland” tells the story of the boom and bust of Maine’s sardine industry, and the hard-working Mainers that caught and packed the fish.

“This is really about those working class people, who worked a hard, gritty, grueling job,” Good said. “And it’s also about what happens when an industry collapses, whether it’s through climate change, or the changes in what people want to buy, or any of the other many reasons.”

Maine’s sardine industry began in the 1870s, after Mainer George Burnham (no relation to the author of this article!) returned from a trip to France with a plan to establish a sardine fishery in Passamaquoddy Bay, similar to centuries-old herring fisheries in Europe. The silvery little herrings were unbelievably plentiful in the bay, and at that point had not been a sought-after catch for Maine fishermen. After some trial and error - Maine’s damp climate did not lend to drying the fish, as the French climate did, but packing them in oil worked beautifully - the first sardine cannery in the U.S. opened in Eastport in 1875.

Over the next two decades Maine’s sardine fishery exploded, and canneries sprung up all along the coast, from Portland to Lubec and all points in between. By the turn of the century, the sardine industry was one of the largest employers of rural people in Maine, many of whom commuted into port towns from their inland villages to work long hours in the canneries, packing hundreds of thousands of the silvery little herring into their distinctive little tins.

Men caught the fish, for the most part, and a few worked in the canneries. Before federal child labor laws were established in the 1930s, children often worked there too. But the vast majority of employees who packed sardines were women. They moved faster, factory owners said, and had more dextrous fingers. In an era before U.S. laws around minimum wage and equal pay, owners could also get away with paying women less.

The packing process also required incredibly fast, repetitive motion – you were paid by the can, sometimes just a few cents - and the use of little scissors to snip off the heads and tails. Most women emerged from their shifts with small, painful cuts on their fingers, and many developed chronic wrist and hand injuries over the years.

Nevertheless, for working class women in Downeast Maine, it was one of the few jobs available to them that didn’t require specific skills or certification. For many of those rural families, it was a financial lifeline.

The PMM conducted listening sessions in former sardine towns in the year leading up to the opening of “Sardineland” in May 2025, hearing stories from former cannery workers about the camaraderie they experienced on the job. They swapped gossip and played pranks on each other. They shared stories about their families. They ate lunch together, shared cigarettes together, wrapped each other’s fingers up when they would inevitably get nicked by the scissors. It was a sisterhood of sorts.

“One of my favorite quotes from the Lubec listening session came from a woman who said that whenever she heard the steam whistle blow - which meant sardines were coming into the bay - she started humming, because that sound meant money,” Good said. “That was the sound of putting food on the table. She could go to work and make money for her family.”

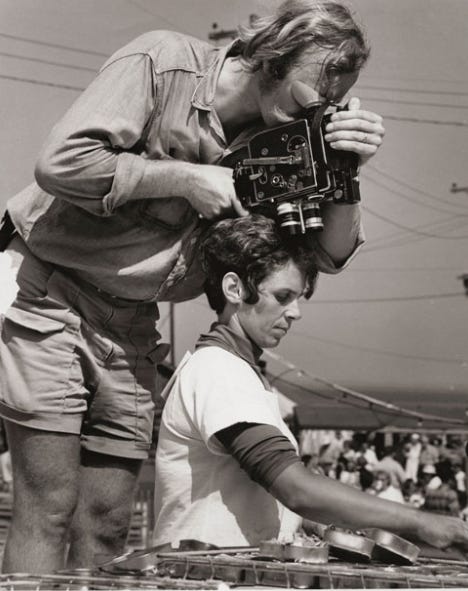

Many of the women took great pride in how fast they could pack. Over the decades, the sheer speed with which they could process and pack the fish became the thing of legends – as well as the flair some exhibited, like tossing a fish up in the air and snipping its tail as it fell back down. In the 1970s, the Maine Lobster Festival in Rockland held the World Championship Sardine Packing Contest, which attracted cannery workers from around the state to compete for the title of the world’s speediest sardine packer.

The winner of that title for eight out of the competition’s 13 total years was Rita Willey, a Rockland woman who, at her peak, could pack an entire can of sardines in under ten seconds. Willey became a minor celebrity, appearing on “The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson” and being feted by politicians like Edmund Muskie and George Mitchell. Willey, now in her 80s, will be in attendance during the PMM’s Sardine Fest this weekend, showing off her sardine packing trophies and telling stories of when she was the fastest packer in the land.

The PMM holds extensive collections about Maine’s sardine industry, many of which were donated by museums, libraries and individuals who worked in or ran the canneries. Among the more unusual items museum staff discovered during the research process for “Sardineland” were things like jars of pearl essence, made by scraping off the shimmery silver scales from fish and then used to create jewelry, buttons and makeup. Staff collected machinery and other items from fishing boats and weirs and from the factories themselves - items often lost or severely damaged as the old buildings sat empty.

At its peak, Maine’s sardine industry rivaled the lobster industry, in terms of its size and economic impact. After World War II, however, the industry began to suffer a bit, as other canned seafood like tuna was gaining in popularity. The Maine Sardine Council, the state-funded sardine marketing organization, promoted the industry all across the country, and even encouraged Vacationland tourists to visit sardine towns to see the industry in action.

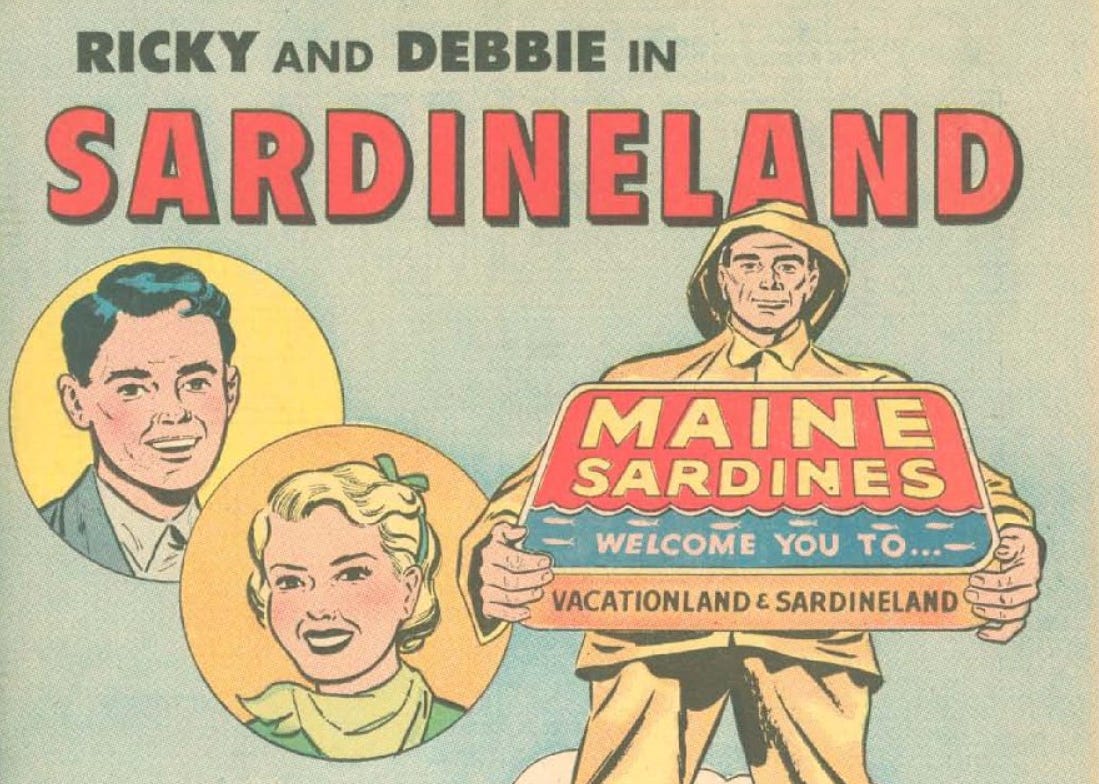

Mark McLaughlin, a history professor at the University of Maine, unearthed a series of comic books published in the 1950s and 60s by the Maine Sardine Council, “Ricky and Debbie in Sardineland,” which shows the titular all-American couple road tripping around coastal Maine, learning about herring and having a very nice time on vacation.

“They’re trying to promote sardines as this healthy option, and they’re also trying to promote it as a source of Maine pride - eat sardines and support Maine,” said McLaughlin, who researches government comic books in both the U.S. and Canada, and will give a presentation on his work at Sardine Fest this weekend. “They’re trying to convince the youngsters that sardines are even kind of cool, in a way.”

As Ricky and Debbie were being wowed by the wonders of sardines, and as Rita Willey was racking up trophies, the industry she’d worked in for 38 years was already well into its decline. By the 1970s, sardines – once one of the most common lunchtime choices for Americans - had fallen dramatically out of favor.

“Sardines were kind of seen as an old person’s food,” McLaughlin said. “And at the same time, the tuna industry is just blowing them out of the water in terms of marketing. Lobstermen are using herring as bait, which is also competition. And, of course, it is readily apparent that overfishing is becoming a big problem.”

Canneries began closing in the 1970s, and by 2000, only a handful were left in Maine. In 2010, the Stinson plant, the last sardine cannery in the U.S., in the village of Prospect Harbor in the Hancock County town of Gouldsboro, shut its doors. The Maine sardine industry was over. Though some have tried to revive seafood canning in Maine - just this week Bold Coast Seafood announced it plans to process lobster and crab at the Prospect Harbor plant - the boom days of the last century are long gone.

Good said one of her big takeaways from their deep dive into this unique part of Maine history is how much of a cautionary tale it is for other extractive industries. Whether through overharvesting, climate change or changing tastes, when a town or region is too heavily dependent on one particular industry, it can be extremely difficult to bounce back once it takes a downtown or disappears outright.

“I think the big story of this is what happens when your extractive industry goes away,” Good said. “You think of oil fields and coal mines, and even here, in Maine, with the lumber industry and paper mills. Some places in Maine have had a really hard time pivoting. Belfast was able to pivot toward a service industry after the canneries and the chicken plants closed, with MBNA and all that. Washington County has really struggled. They lost the big economic driver. There’s still a big gap to fill.”

It also shows how hardy, strong-willed, blue collar Mainers remain proud of the work they did in previous eras, and how their legacy can be seen throughout the state. For better or worse, there are few towns in Maine that haven’t been shaped by the industries of the past - lumber in Bangor, paper mills in places like Millinocket or Bucksport, the textile industry in Waterville, and sardines in towns all across Washington County. How a place moves on after such a life-altering change is the real story - still being written, decades later.

Sardine Fest is set for 10 a.m. to 4 p.m., Saturday, Oct. 4 at the Penobscot Marine Museum in Searsport. Activities include live music, sardine can decorating, a sea life touch tank, a sardine tasting, sailing demos, and a talk with the famous Rita Willey. Admission is free.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2WTgylPfaso

" I've worked all my life in the cannery shed

And if I am dying or you think I am dead

Don't bury my bones but put me instead

In a can in the cannery shed"