INTERVIEW | Loren Coleman: The hopeful cryptozoologist

"They want to see the world that could be, or that maybe is."

By spring 2026, Loren Coleman is bound and determined to have the jumbled array of artifacts, models, replicas, photos, paintings and other ephemera that he’s amassed over the decades organized and presented beautifully in his new Bangor location for the International Cryptozoology Museum.

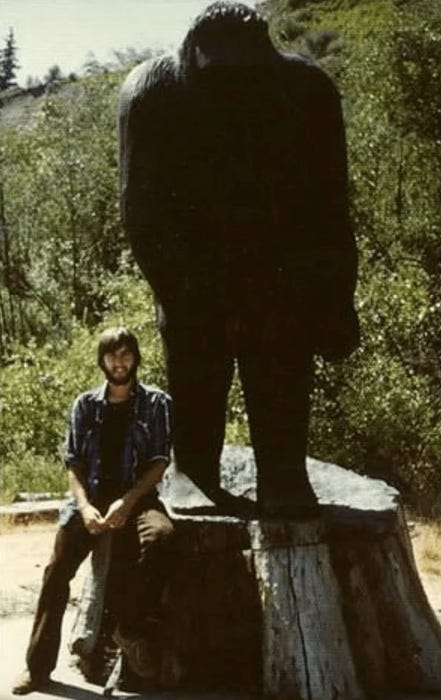

Right now, however, those items - from a 2001 footprint cast taken from the (allegedly) extinct Thylacine to massive sculptures of Bigfoot, Moai heads and the Yeti - are all patiently waiting to be put on display at the museum’s new building at 490 Broadway, a former bus station and taxi depot that Coleman has spent the past four years painstakingly restoring. The building, a rare example of mid-century modernist architecture in Maine just across the street from an I-95 ramp, is a “hidden gem,” as Coleman calls it, and stands out amid the banks, stores and fast food joints that line Broadway.

The new, greatly expanded location for the museum is the culmination of more than 60 years of work from Coleman, who is the author of more than 50 books on cryptids, and who is regarded by his colleagues as a legend in the cryptozoology field. Amid the motley international community of enthusiasts, researchers, folklorists, ghost hunters, Bigfoot hunters, UFOlogists, spiritual seekers and old-timey hucksters, Coleman has remained a calm, steady presence - at once skeptical and rational, and endlessly curious and hopeful about what remains unknown or hidden out there in the wide world.

He’s made Maine his home for more than 40 years, and opened the first version of the museum in 2003, in a full-to-bursting residential home in Portland. When he opens the latest version of the museum in Bangor in April, it’ll finally house Coleman’s entire collection - between items and books, it numbers in the many thousands - all under one roof.

Coleman is, understandably, very excited. I caught up with him on a frigid Saturday, where we talked about Streamline Moderne architecture, his childhood love of the Yeti, and what draws people to the world of cryptozoology.

Can you tell me about your earliest experience being fascinated with this topic? Where does it come from? When did it start?

I can tell you the exact date. March 20, 1960. On our local TV station in Decatur, Illinois, where I grew up, they aired a movie, “Half Human,” a Japanese movie that was released as “Beastman Snowman” in Japan. It was all about the Abominable Snowman, or the Yeti. These characters are up in the mountains, and they find a Yeti, and of course, they kill it. They kill a baby Yeti too. It was supposed to be a scary movie, but to me, it was heartbreaking. I was always obsessed with science and learning every animal, but I’d never heard of a creature like a Yeti. They showed the movie again the next day, and I was hooked.

So the Yeti was your gateway to this world? It’s kind of your keystone cryptid species.

Yeah, the Yeti will always have a very special place in my heart. When I went back to school the Monday after I saw the movie, I asked my teacher about it, and he pointed me to a World Book about this expedition in the Himalayas that had just happened. I wrote to them, and they sent me a flag from the expedition, which of course is in the museum. And I just started doing tons of research and writing to everybody I could find on what was then known as “romantic zoology,” which I think is a much cooler term than cryptozoology. Cryptozoology wasn’t even yet coined as a term in 1960. I became well known to all the reference librarians at my library. I was already reading books by Charles Fort, whose point of view was that if someone tells you something doesn’t exist, look behind it. Start asking questions. When I graduated in 1965 someone wrote in my yearbook, “Are you really going to go look for the Abominable Snowman?”

How has this field changed, in all the years you’ve been doing research and connecting with people? You’re known internationally as an expert - not just on various cryptids, but on the cryptozoology community as a whole.

You know, people call me a “legend” in the cryptozoology world. I would never call myself that. But I think I’ve been around long enough to learn something. I think one thing that’s served me well is that I was a very early adopter of the web. I’ve had an online presence since the mid-1990s, back when I worked at the University of Southern Maine. I’m able to connect with the older generations, and the newer ones coming up. I think that people today are just as interested in these things as people before - they just have new ways to access information.

Do you think there’s a thread that connects all the different types of people that are fascinated by cryptozoology? Is there one defining characteristic?

I think people that are into cryptozoology fall into a few different camps. There are people that are into what I call the “flesh and blood” world, as in they are looking for actual, physical proof of various cryptids existing. There are people that are into the paranormal, who are interested in ghosts and UFOs. There are the kind of woo-woo people, who go off into lots of different, unique directions, or people that are spiritual. People might be surprised to learn that a lot of cryptozoologists are Mormon. There’s a thread in the LDS church that’s all about searching for evidence. They want to see the world that could be, or that maybe is.

There’s also a type of person that is in it for attention, or money, or fame. I’m not interested in that. If you just want to have a Bigfoot TV show or something, that’s not for me. I generally meet a lot of very bright people who are just hopeful that certain animals may exist. That’s the kind of cryptozoologist I categorize myself as. I remain hopeful.

What do you think cryptids tell us about ourselves? Do you think they reflect something about human nature - our fears, our identities, our history?

One thing that I always point to is how scientific consensus about the origins of humanity has changed over the years. Scientists used to think it was this one straight line to modern humans. Today, we know that Neanderthals and Denisovans interbred with humans. They co-existed. It’s still in our DNA. So if that is true, what else might be true?

I think the thing that binds everybody - aside from those people that just want their 15 minutes of fame - is curiosity. People that just want to understand more about the world. They want to learn. They want to tell stories. I love it when little kids ask me about Bigfoot. I’m interested in every approach to it, even if it’s not my personal preference. I think people often think that cryptozoologists have all drunk the Kool-Aid and believe everything. You can be open to these ideas and not actually believe it! You can be interested in every aspect of it and still be skeptical.

You have a kind of anthropological approach to things, it seems like.

I’m just as interested in how we portray cryptids. That’s why I have a lot of toys in the museum. Prior to 1964, the Yeti looked a lot more like Bigfoot. Then, when “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” came out, all the Yetis became white, like the Bumble.

Bigfoot always ends up looking like “Harry and the Hendersons.”

Which is quite different from how someone like Harvey Pratt, who was a Native American artist who drew Sasquatch. His Sasquatch looks much more human. His concept was that they are all humans - just hairy. I want to showcase those differences in the museum. I want people to really learn something. And have fun while doing it.

You’ve had the museum in Portland in one place or another for over 20 years now. What’s bringing you to Bangor?

Well, it probably won’t surprise you to hear that it’s gotten increasingly expensive to rent or do anything in Portland. And, quite frankly, our space at Thompson’s Point - which is a very nice development, don’t get me wrong - but it’s just not very big. And it’s gotten pricier. It’s really squeezing us. So being able to get way more bang for our buck in Bangor was very appealing. We’ve actually been living up here for a few years now, and Jenny, my wife, grew up in the area. And then, of course, we found this building.

It’s so funny, because I’ve lived in Bangor for ages, and I drive down Broadway multiple times per week, and for most of that time I’ve hardly even looked at this building. But you saw something in it! What was that?

To be honest, I saw the real estate listing [laughs]. What struck me, though, was that it might appear to be a kind of warehouse, garage looking place, but in reality was a true hidden gem. Specifically, the fact that it appeared to be designed in the Streamline Moderne architectural style, which is extremely rare for Maine. The price was right, so we bought it. And then I started doing a ton of research on it, and the folks that owned it before - it was a bottle redemption center and a taxi company - really had no idea what they had.

Anyway, it took forever but we finally figured out who designed the building, and that it was built in 1945 as a bus station and a garage for Hasey’s Maine Stages. They were a bus company that came along after the railroads were declining, and they sent buses up into the north woods, to all the sporting camps up north. Broadway was built on an old stagecoach route, hence the name. It’s pretty interesting that they opted for this very modern looking building. I still don’t really know why they did that, even though a lot of bus stations and airports and transportation buildings in other parts of the country had the Streamline Moderne style. It was just never really used here in Maine. Maine can sometimes be a little behind the times [laughs].

It’s pretty unusual, which is probably why you worked to get it on the National Register of Historic Places.

Exactly. It’s a very rare example of modernist architecture in Maine. And it was used for such a utilitarian purpose - first a bus station, and then it was a car dealership for Packard cars, and then the taxi depot and the redemption center. I actually found an old Packard to display outside. I know it’s not cryptozoological, but I am trying to ground the museum in this kind of look, design-wise. I want the building to also be part of the attraction.

I mean, you could say that the Packard is the car that the people that first saw the Mothman in West Virginia were driving in. Or it was one of the cars on the bridge that collapsed, that Mothman was warning them about. Make it a whole thing.

[Laughs] That’s a thought! You know, I actually have a scale recreation of the Mothman bridge in the collection.

Of course you do.

This is such a fascinating look into the world of cryptozoology and Coleman's dedication to it. I love how he balances skeptisism with genuine curiosity--its rare to find someone who can remain hopeful without being naive about these things. The fact that he traced the building's history back to a stagecoach route and found Streamline Moderne architecture in Maine is just as intresting as the cryptid collection itself. Really looking forward to visiting when it opens in Bangor.